Friedrich Nietzsche once said, "It is my ambition to say in ten sentences what others say in a whole book."

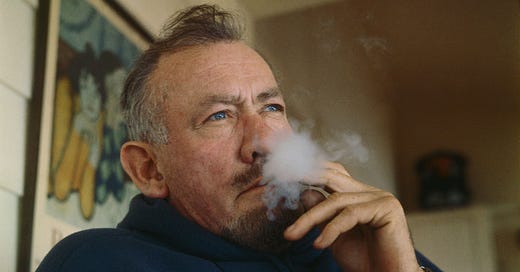

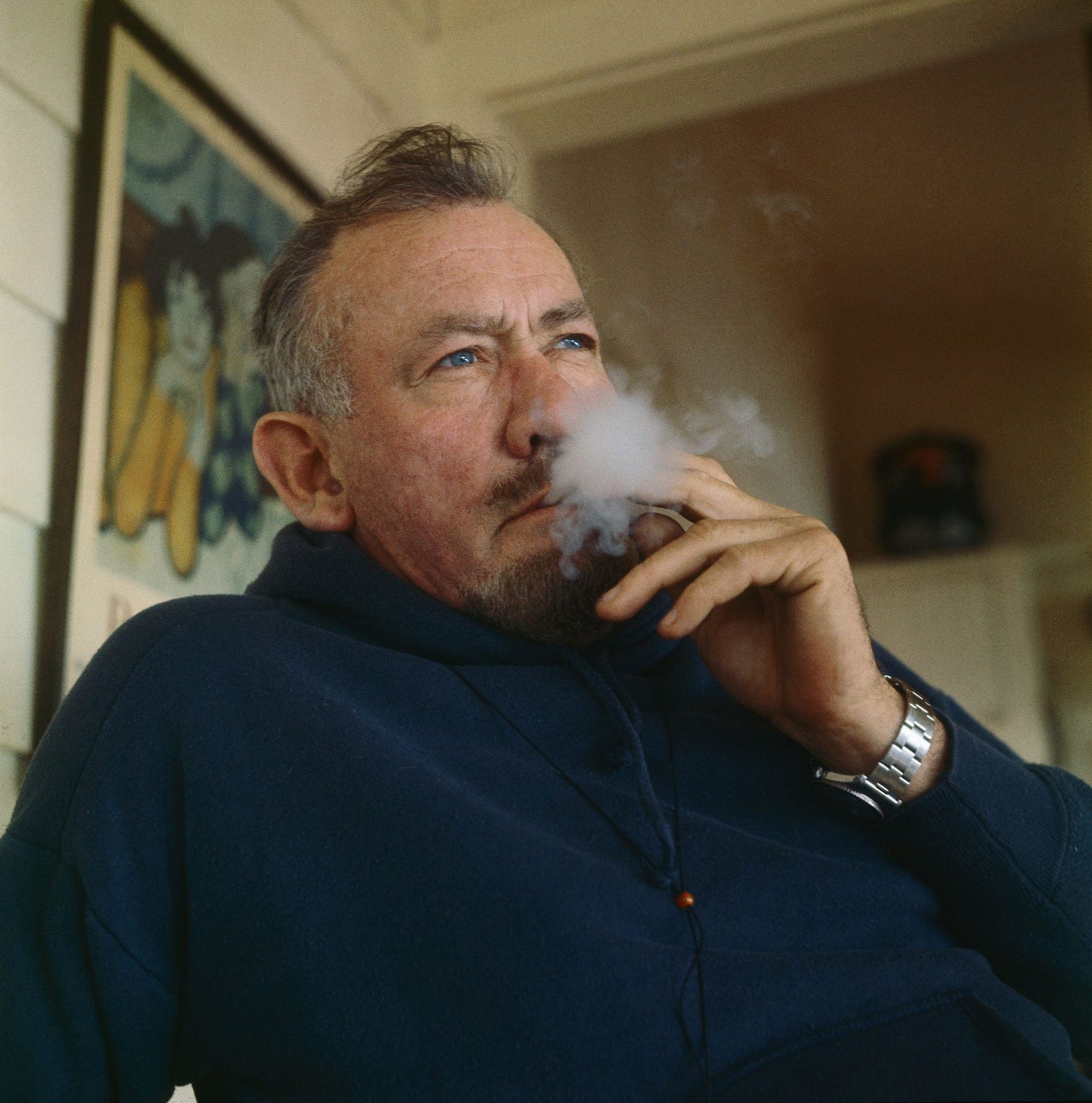

If there was ever a writer of fiction who embodied this ambition, it was John Steinbeck. The first time I read East of Eden, I was so thoroughly impressed with his character introductions, I felt implored to know exactly what magic he used. In a paragraph, he could paint a character more nuanced, more vivid, and more real than most any author can achieve in 300 pages. Thus, East of Eden became my all time favorite novel. So below, I’m going to analyze exactly how he wrote and what authors can learn from his mastery.

Cyrus Trask

“Adam’s father Cyrus was something of a devil—had always been wild— drove a two-wheeled cart too fast, and managed to make his wooden leg seem jaunty and desirable. He had enjoyed his military career, what there was of it. Being wild by nature, he had liked his brief period of training and the drinking and gambling and whoring that went with it.” p. 24

Steinbeck utilizes direct, evocative language for Cyrus. Devil, wild. He then lists his habits to back the claims, his humorous bravado, displaying a man of a strong malevolent spirit.

“But Cyrus had vitality and swagger. While he was carving his beechwood leg and hobbling about on a crutch, he contracted a particularly virulent dose of the clap from a Negro girl who whistled at him from under a pile of lumber and charged him ten cents. When he had his new leg, and painfully knew his condition, he hobbled about for days, looking for the girl. He told his bunkmates what he was going to do when he found her. He planned to cut off her ears and her nose with his pocketknife and get his money back. Carving on his wooden leg, he showed his friends how he would cut her.” p. 25

Again, he’s described plainly and simply, but these simple descriptions are thrust into example, how Cyrus had, after an amputated leg, contracted gonorrhea from a prostitute and plotted his violent revenge. The reader knows Cyrus’s character through bold description, wild action, and his thirst for blood, all in one paragraph.

Cal Trask

“Cal did not question the fact that people liked his brother better, but he had developed a means for making it all right with himself. He planned and waited until one time that admiring person exposed himself, and then something happened and the victim never knew how or why. Out of revenge Cal extracted a fluid of power, and out of power, joy. It was the strongest, purest emotion he knew. Far from disliking Aron, he loved him because he was usually the cause for Cal’s feelings of triumph. He had forgotten—if he had ever known—that he punished because he wished he could be loved as Aron was loved.” p. 404

In this retelling of Cain and Abel, Steinbeck allows the reader something the Bible does not: interiority. For the first time, we have a sense of the psychology of the alleged future murderer. We see that the young boy, even at the age of 8, knows other prefer his brother, because Steinbeck tells us directly. Then there’s a sympathy for the child, for he needs to develop a defense to make it not hurt. In his hurt, Steinbeck gives Cal’s reaction: he extracted that joyful power, an evil yet understandable coping mechanism for his rejection. And yet, he loved his brother because he was what he wished to be. And because he couldn’t be him, he lashed out on those who rejected him. It’s a beautiful depiction of a boy’s early knowledge of his rejection and how being unloved affects his mind.

Tom Hamilton

“He was born in fury and he lived in lightning. Tom came headlong into life. He was a giant in joy and enthusiasms. He didn’t discover the world and its people, he created them. When he read his father’s books, he was the first. He lived in a world shining and fresh and as uninspected as Eden on the sixth day. His mind plunged like a colt in a happy pasture, and when later the world put up fences he plunged against the wire, and when the final stockade surrounded him, he plunged right through it and out. And as he was capable of giant joy, so did he harbor huge sorrow, so that when his dog died the world ended.” p. 52

Off the bat, Tom is a frenetic boy, with emotions quick and powerful as bursts of lightning. He’s enamored with the world, curious, rule breaking, headstrong, showing a lovely simile of a young horse leaping through the fields breaking free of its fences. But this boy exists at the extremes, and Steinbeck contrasts that ecstasy with a boy mourning his dog, feeling each emotion deeply.

“Tom was as inventive as his father but he was bolder. He would try things his father would not dare. Also, he had a large concupiscence to put the spurs in his flanks, and this Samuel did not have. Perhaps it was his driving sexual need that made him remain a bachelor. It was a very moral family he was born into. It might be that his dreams and his longing, and his outlets for that matter, made him feel unworthy, drove him sometimes whining into the hills. Tom was a nice mixture of savagery and gentleness. He worked inhumanly, only to lose in effort his crushing impulses.” p. 52

Here, we see Tom as an adult, with the gaiety of his father, but more risk taking, more darkness. He was a man of large sexual desire, and even larger conscience. And with these two opposing forces, Tom felt himself unworthy of a woman and would whine in the hills at night, scourging himself for his sins. As a deeply moral man, a deeply empathetic character, Tom finds the only way to distract his impulses through his work. From the get-go, he’s a man internally at odds.

“Tom did not have his father’s lyric softness or his gay good looks. But you could feel Tom when you came near to him—you could feel strength and warmth and an iron integrity. And under all of this was a shrinking—a shy shrinking. He could be as gay as his father, and suddenly in the middle it would be cut the way you would cut a violin string, and you could watch Tom go whirling into darkness.” p. 321

Here, Steinbeck juxtaposes Tom’s external character with his self-perception. As an honest, strong, loving man, there was a ruthless self-criticism, one that could erupt from within and send him spiraling into the proverbial darkness.

Overall:

Steinbeck utilizes many different techniques:

For Cyrus, forward description and narrative examples of his wild behavior.

For Cal, a uniquely unbiblical introspection of a rejected young boy, and the evil developed within based on the world’s treatment of him. A contrast between him and his brother, an anger with the pain, a joy with the anger, a guilt at the joy.

For Tom, a man oscillating between bipolar extremes, from joy and passion to a dark guilt, from bold action to torturing regret.

But they all relatively follow the same formula:

Direct characterization through adjectives, relation to life, disposition

Examples of idiosyncratic behavior and creative metaphors to back these claims

How the world treats them

How their personalities react/change in relation to their past

How they feel about their reactions (often guilt, but grandiosity for Cyrus)

So what makes them real? What makes them interesting? The beauty of Steinbeck’s characters lies in their contradictions. Each of the characters are unique. They’re anomalous. They are each bold embodiments of different spectrums of humanity, each shaped by their worldly experiences, their wild pasts. Cyrus and his service, Cal and his brother, Tom beneath the shadow of his father. We see realistic reactions to these events, anecdotes, feelings about their own reactions, reasons for being.

A few well-chosen words capture their essence. They teeter between the extremes, they’re bold, they’re passionate, they’re human. And with these adamant descriptions, these memorable stories, and these reactionary internal contradictions, Steinbeck crafts some of the most memorable characters in fiction.

Great analysis and a very pleasant read. Thoroughly enjoyed your points on this masterful book!

Nicely done. Have you read Steinbeck's *Journal of a Novel,* the account of the daily drafting of *East of Eden*?

(Sheesh, I've recommended it so much that now *I* want to reread it.)